Discovery against parties and non-parties in the context of estate proceedings, particularly Family Provision Act proceedings, does have its place.

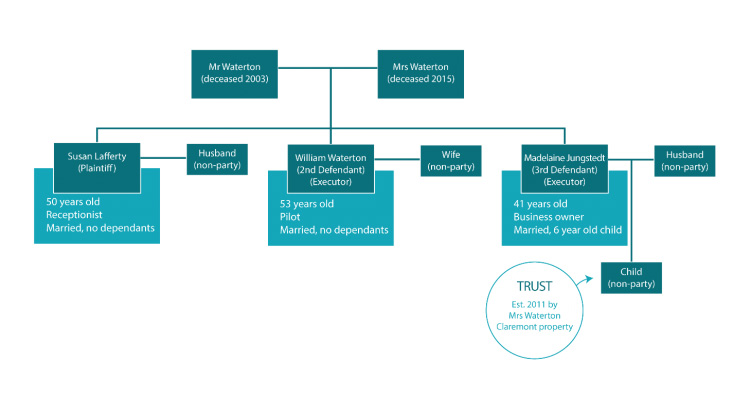

In Lafferty v Waterton (No 2) (Lafferty’s Case) a certain level of discovery was permitted. Mr Waterton died leaving his entire estate to his wife, Mrs Waterton. Mrs Waterton promised her three children (Susan, William and Madelaine) she would leave her estate, including what she had inherited from her late husband, to them in equal shares.

Instead, Mrs Waterton made substantial gifts to William and Madelaine during her lifetime. She established a trust holding property for a grandchild. As a result, little remained of Mrs Waterton’s estate upon her death. Susan claimed compensation because she had relied on her mother’s promise regarding her Will.

Both Susan and William made numerous applications for discovery, including:

- Susan’s application against the deceased’s professional advisers, regarding:

- The circumstances of the creation of the Mr Waterton’s Will. The Court did not consider this was relevant.

- Legal advice given to William and Madelaine. The Court found that the professional adviser was not the appropriate party to give that evidence. The proper party was the person with an interest in the documents, who deserved an opportunity to object to their production. In this case, that was William and Madelaine, who had procured the advice.

- Susan’s application for fee records held by a grandchild’s school. These were found to be relevant, as the Plaintiff had alleged the deceased provided gifts in the form of school fee payments. Whilst the Court noted the importance of assessing the burden upon the discoverer, Fee records were considered sufficiently easy to extract from the school’s database.

- William applied for discovery against Susan’s husband. As a non-party, the Court said that the husband could not be expected to devote substantial time to discovery, nor waive his right to confidentiality without good cause. The Court ordered only two of the four requested items of information were appropriate to be discovered – the remaining information being too burdensome.

This case makes it clear that discovery, including third party discovery, will ordinarily only be granted where the evidence sought:

- is relevant;

- is requested from the appropriate party; and

- does not impose a disproportionate compliance burden upon the non-party.

What about discovery in matters that do not normally attract such orders?

Discovery in Family Provision Act Claims

The Supreme Court practice directions note that the Court will not usually order discovery in Family Provision Act applications.

Discovery may appear necessary when, for example, an estate consists of a 100% shareholding in a substantial private company. The circumstances of that company – including its constitution, its accounts, its management reports and the arrangements it has with its financiers may have a significant effect on the value of any company shares and, therefore, the plaintiff’s claim (as it will form the basis of any calculation of what the plaintiff was left under the Will). To fully understand the composition of the estate assets, access to bank and other financial documents may appear necessary. The directors of the company may initially refuse to provide such documents on the basis that the information is confidential to the company.

Some solicitors believe that a subpoena may be the answer to the above problem, but documents produced by subpoena can be problematic to get into evidence in proceedings commenced by originating summons, normally heard on affidavit.

Discovery may also appear necessary when the plaintiff alleges that they are of modest assets (and therefore in need of further provision) when publicly available information suggests otherwise. This was the case in Kiernan v Cranston & Purcell[1]. The defendant sought an order that the plaintiff undergo medical examinations, as the plaintiff’s involvement in complex business dealings cast doubt on the extent of his alleged permanent brain injury.

The court carefully considered the situation, confirming that discovery is not generally ordered in Family Provision Act applications, and that an order for discovery requiring medical examination would likely be unprecedented. The Court concluded that sufficient information could be obtained by cross-examining the plaintiff on the disparity between the mental capacity he alleged, and his comparative business success.

Conclusion

To make an order for discovery, the court must be satisfied concerning the likely contents of the document, whether it will be relevant to the matter, and the principles of case management. Where the burden of locating, sorting, and redacting irrelevant evidence is too high, the court will refuse to make an order for discovery. Where the evidence is information a non-party has provided in a professional capacity to a client, it is unlikely discovery will be ordered.

When the discovery application is made in the context of a Family Provision Act claim, prepare for a difficult argument. The court will likely consider that there are simpler methods to resolve allegations made by the plaintiff.